Every now and then a concept comes along that resonates very strongly with what I perceive to be key issues in operations in general, and supply chain in particular. One of these is the seminal work by George Stalk of Boston Consulting Group titled Time—The Next Source of Competitive Advantage published in July 1988 in which he states that:

Today, time is on the cutting edge. The ways leading companies manage time - in production, in new product development and introduction, in sales and distribution - represent the most powerful new sources of competitive advantage.

Unfortunately Stalk decided to name the book he co-wrote on the topic as “Competing Against Time” which isn’t the point, although the subheading “How time-based competition is reshaping global markets” rescues the concept, which is really about competing against the competition with time. It is all about being more agile, more responsive, to real conditions. Stalk sets out some Rules of Response very clearly:

- The .05 to 5 Rule Across a spectrum of businesses, the amount of time required to execute a service or to order, manufacture, and deliver a product is far less than the actual time the service or product spends in the value-delivery system

- The 3/3 Rule During the 95 to 99.95 percent of the time a product or service is not receiving value while in the value-delivery system, the product or service is waiting. (Stalk breaks this out into 3 components of waiting, hence the 3/3.) The amount of time lost is affected very little by working harder. But working smarter has tremendous impact.

- The 1/4-2-20 Rule For every quartering of the time interval required to provide a service or product, the productivity of labor and of working capital can often double. These productivity gains result in as much as a 20 percent reduction in costs.

- The 3 x 2 Rule Companies that cut the time consumption of their value-delivery systems turn the basis of competitive advantage to their favor. Growth rates of three times the industry average with two times the industry profit margins are exciting – and achievable – targets.

All too often though people get the impression that these rules are only applicable in the short term. They are not. The issue of responsiveness in operations is driven by the latency of the information and the time it takes to respond. In other words, the time to detect that something of significance has happened and the time to respond to the change, or correct the discrepancy. Reducing either of these will have a dramatic effect on a company’s competitiveness, whether this is a short term detection of demand change that requires rescheduling manufacturing or a longer term change in technology that requires the purchase of new manufacturing capacity. Terms such as VUCA – Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity - or PDCA – Plan, Do, Check, Act - don’t excite me because they are focused on removing volatility and complexity, usually promoting ‘stability’ at the cost of responsiveness, whereas Stalk’s concepts are all about being responsive, being agile. To me this is the correct emphasis. While of course there is an overlap in that a decision or manufacturing process that is overly complex will result in longer lead times, it is the overall sentiment of complexity and volatility being ‘bad’ expressed in VUCA and PDCA with which I disagree. As I wrote in a previous blog from the 2011 Gartner Supply Chain Conference:

I say embrace VUCA. Accept that it is the new norm. Resistance is futile.

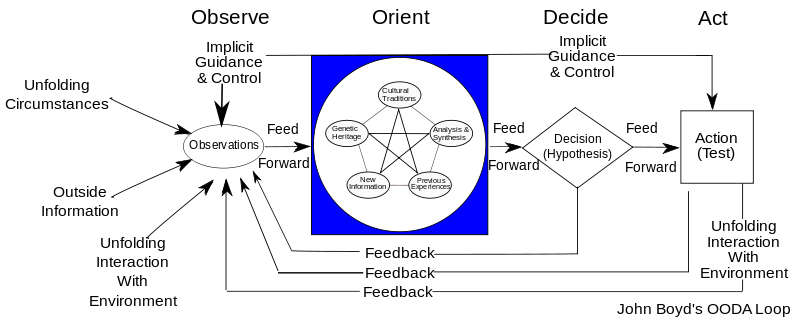

Similarly, Deming’s idea of PDCA is all about process improvement, it is about ‘managing’ complexity and ensuring ‘consistent’ processes. Again, I am not saying that these are bad approaches in and of themselves, only that they are insufficient. Knowing that you are performing a process consistently doesn’t mean that you are performing it well. It is like assuming that if you throw everyone in jail who has committed a crime that we will live in a crime-free environment. Far more interesting to me is the OODA - Observe, Orient, Decide, Act - idea from the US military strategist Colonel John Boyd.

The steps of the OODA loop are:

While at first this may seem to be very similar to VUCA and PDCA, the key point to the OODA loop is that:

Time is the dominant parameter. The pilot who goes through the OODA cycle in the shortest time prevails because his opponent is caught responding to situations that have already changed.

In other words reduce the time to detect and the time to respond. To put this into supply chain speak, it is all about:

- Visibility – having access to the state of the supply chain across a wide span of operations, especially in outsourced environments, in order to detect misalignments

- Alerting – knowing or calculating the impact of misalignments on key financial and operational metrics in order to understand the severity of the issue

- "What-If" – working with others in the supply chain to come up with alternatives and evaluating these quickly

- Collaboration - to reach a consensus on the best course of action that reduces risk while increasing performance

Another absolutely key concept expressed by Boyd is the need for ‘human judgment’, for the system to act as an organic whole to adapt to situations as they unfold at the location at which they unfold. Having long chains of command that force front line people to get approval from HQ is antithical to this idea:

… large organizations such as corporations, governments, or militaries possessed a hierarchy of OODA loops at tactical, grand-tactical (operational art), and strategic levels. In addition, he stated that most effective organizations have a highly decentralized chain of command that utilizes objective-driven orders, or directive control, rather than method-driven orders in order to harness the mental capacity and creative abilities of individual commanders at each level. In 2003, this power to the edge concept took the form of a DOD publication "Power to the Edge: Command...Control...in the Information Age" by Dr. David S. Alberts and Richard E. Hayes. Boyd argued that such a structure creates a flexible "organic whole" that is quicker to adapt to rapidly changing situations. He noted, however, that any such highly decentralized organization would necessitate a high degree of mutual trust and a common outlook that came from prior shared experiences. Headquarters needs to know that the troops are perfectly capable of forming a good plan for taking a specific objective, and the troops need to know that Headquarters does not direct them to achieve certain objectives without good reason.

These are key concepts we at Kinaxis have been promoting for a long time. Every second that we waste in making a decision is a minute less that we have available to actually respond to situation. In sports, reaction time is a well recognized competitive advantage. Reaction time is coupled with the ability to ‘read the game’ and, for example, to call audibles at the line of scrimmage in American football. (I have always felt more comfortable with ‘European’ sports, such as soccer, that are a lot less structured and orchestrated precisely because the players have a lot more decision making power.) So in the end perhaps Stalk’s title “Competing Against Time” was correct, but this is a process efficiency perspective. I still prefer the OODA concept of competing with time because this is about process effectiveness.

Discussions

Nice post.

In my business, I have noticed that the OODA loops must be completed faster and faster and faster with more complex data streams than in previous years. That is, the rate of change is increasing and the time window to complete an OOAD shrinks. That is why my greatest asset is a planner who can look at the flow of data like in the movie the Matrix and instantly see the impact of deviations, whether it be demand, supply or buffers.

Interestingly we had Paul Carbonneau (from McKinsey) and Kevin O'Marah (originally from AMR Research & Gartner) speak at our conference. A key theme both of them brought out is the type of person you need in the supply chain, and both of them referred to the analytical skill that you mention: "...can look at the flow of data ... and instantly see the impact of deviations..."

While this is correct, this is the starting point. This is knowing that something is 'not right'. This is the Lean principle of 'time to detect'. Getting inside the OODA loop requires the other Lean principle: 'time to correct'. Undoubtedly the same skills are required to reduce the 'time to correct', but correction also requires collaborative skills.

Where OODA and VUCA are related is that, as you point out, the rate of change is increasing leading to an increase in volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity.

Thanks for the response.

Regards

Trevor

Great article. As a recent graduate, I am always looking to further my understanding of the industry. I liked your point that both responding to issues AND solving issues quickly is important. Often, it is possible to plan for/identify a problem early on, but only once that problem is solved can the system move forward. All the innovative solutions in the world mean nothing if they cannot be quickly/cost-effectively implemented.

I think the development of GLS (geolocation systems) nanotechnology will serve to respond better to visibility issues in the supply chain. As well, the ability to individualize and track goods on a more intricate level may provide the necessary information to solve issues faster as they arise. The question is, how do you train people to excel with the OODA loops? That response time is the human element and maybe the hardest to tackle. And as Jim said, "the OODA loops must be completed faster and faster and faster with more complex data streams than in previous years." So, how does a company make its employees competitive in the fight against time?

I see concepts such as Complex Event Processing (CEP) being used to separate 'signal' from 'noise', with humans being directed to the 'signal' and systems dealing with the 'noise'. Humans are very good at understanding nuance and compromise so use them for those tasks, and let machines take care of the mundane tasks, which will be the bulk of the events anyway.

This provides true 'management-by-exception' capability because in most cases it is the impact of the event that determines the severity of the event, not the event itself, even if certain control limits were violated. This is what we have been focused on for a long time and is behind our strap line of Plan-Monitor-Respond.

Regards

Trevor

Your question was how to make one's employees competitive in the fight against time.

So many paradoxes come into play here, but the first one I worked on was that in order to speed things up, sometimes you have to slow things down.

Number 7 on Covey's list of 7 habits is sharpening the saw. When I sharpen my saw, I don't just whip out my file--I try to sharpen it on a molecular level. The paradox is that this approach carries high risk in worrying important stakeholders, such as the customer, who usually is totally unconcerned about your efforts to make life easier for everyone. Loss of customers usually results in the loss of employee headroom that would allow Slow Sculpture to bring about the quantum leaps everyone desires, but no one wants to work for. (In the analog era, sound meters used a needle to show recording levels. The level between zero distortion and 3%--the maximum allowed--was referred to as "headroom".)

I always had this silly idea that labor was an asset, not a cost, and used the headroom to build tools and mindsets in my battle against time. I did this not only by using sweat equity to build improvements and efficiencies into my modest DC, but by stealth management and underground instruction. (I was officially reprimanded for overtraining my front-line crew--but they couldn't stop me from one-on-one mindset construction.)

Of course, to pull this off, you need a highly tenured crew. I had a small crew, but 2/3 of them had an average of 14 years in the mix. They understood the need to change and adapt, but carried with them what I now call the Mindset for Success. I think it used to be called "the will to succeed."

You can't get that with temps or outsourcing: ya gotta grow yer own.

Sorry for running on, but time is the greatest enemy, and your only ally. You can't defeat it, but if you can create time-travelers with your front-line crew, you can take some interesting rides, and once in a while, even accomplish the impossible.

Leave a Reply